Twelve months ago I joined the BBC to work on the design system of one of the organisation’s key tech platforms, WebCore.

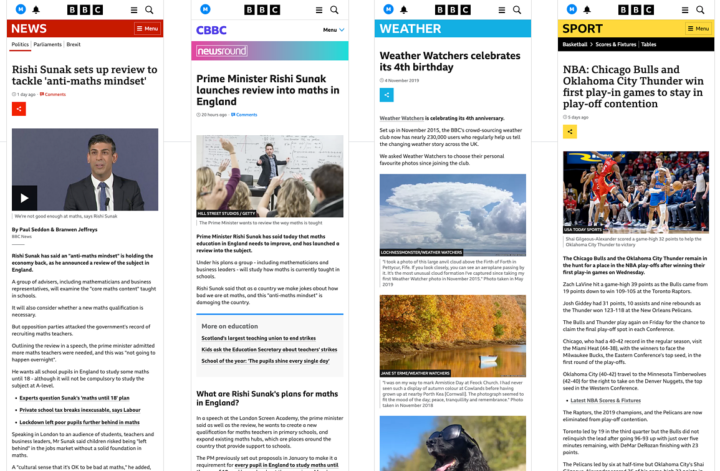

WebCore powers the vast majority of web experiences including such as News, Sport, Bitesize etc.

Unlike other design systems that are versioned and installed, the WebCore Design System is built into WebCore and is viewed as the actualisation of the BBC’s Global Experience Language. In essence, this means that if you are building on WebCore, you have no choice but to use the design system.

This means 250+ individuals working across 20+ teams and, more importantly, the millions of users they serve rely on the WebCore Design System.

I’ve shared this information to provide a bit of context.

From this point on, I will be talking more generally about design systems with the odd reference to what we’ve done as a team this year.

1. Design systems are an essential part of modern development and design practices

If you work in a large organisation, the chances are you either have a design system in place or badly need one.

Having product teams costs money. Having product teams repeatedly solve the same problems is a massive waste of money.

Enter the design system.

I like to think of a design system as a collection of LEGO blocks, with each block representing a problem that’s been already been solved by the organisation. The blocks are then available to other teams in the organisation who, as a result of not having to reinvent the wheel when deciding the design or code of a component such as a button or an accordion, can move faster or spend more time on innovation.

2.There’s huge potential for accessibility wins

If you are committed to accessibility (and you definitely should be), then you should view a design system as a powerful mechanism for change or improvement across an org.

If each component, as a pre-requisite for entering the design system, has been designed with accessibility in mind and rigorously scrutinised against the WCAG standards this will result in each team that uses that component benefitting from that initial a11y good practice.

The opposite of this can of course be true. That is why it’s essential for design systems to prioritise accessibility. Good work done at the point of entering the system can then act as a trojan horse, carrying good practice across the wider business.

There’s also a potential for design systems to prioritise a11y improvements that might otherwise never see the light of day.

For example, our team spent a quarter ensuring our components, where possible went above the legal requirement and into WCAG’s enhanced AAA standard. We were able to roll these changes out globally in a single release which meant that each team that used these components, and the BBC audiences that interact with them instantly felt the benefits of these changes. I very much doubt these nice-to-have / above-and-beyond style changes would have made it to the top of so many team’s hectic backlogs and so, in reality, were only made possible through the existence of the design system.

3. Research is key

As the product person in a design system team, standard product principles apply.

You’ll want to focus on improving performance and driving meaningful outcomes by solving the right problems.

However, the problems your design system faces are more than likely unique to your business or to the extent to which your design system is or isn’t being adopted by the wider business.

For that reason, we need to be conducting research, and plenty of it.

Luckily for design system teams, our users are in the building. This means getting access to people, setting up your own user interviews and really getting under the skin of what is and isn’t working for your design system users is highly achievable.

Embedding a culture of research into the team was one of my key priorities.

The act of conducting extensive research has been hugely beneficial in a number of ways.

- It’s helped us to figure out where we should focus our efforts

- It’s brought us closer to our users, on many cases on first name terms. ie short feedback loops

- It’s in the process of helping us define a product strategy that will allow us to communicate to ourselves, our users and the wider business how we see our design system evolving in the coming 12-24 months.

4. People are your product too

Personally, I’ve not done product in a use case quite like design systems.

By that I mean, you don’t really build a thing.

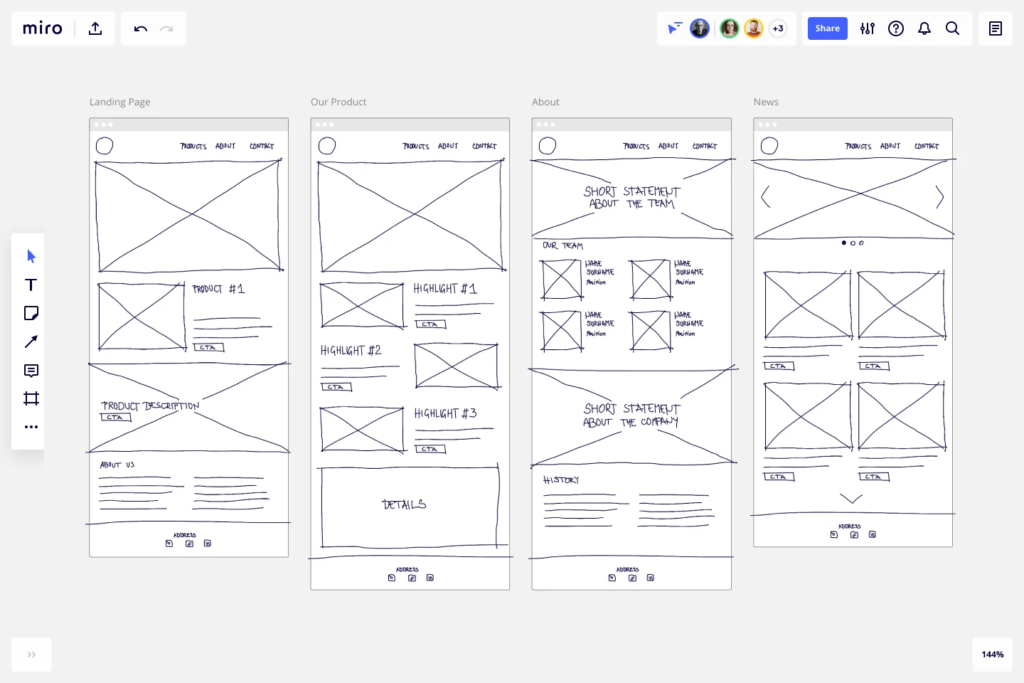

Yes, of course there are assets. You’ll likely have a Figma library, perhaps Storybook and some form of documentation site. And yeah, as a central team you may from time to time build or perform maintenance on some components.

But what you’re actually building is a system, a culture, a way of working. And with that people aren’t just users of your product, they are your product.

For that reason I’ve come to the conclusion that the people that use your design system are just as much a part of the product as the assets themselves. And if you aren’t successful in getting users to build into the system and make it part of their daily working life, you don’t actually have a design system. You just have assets.

If you just make it, they won’t come!

You have to make it easy as possible to use the product, crystal clear on the purported benefits, and you have to be prepared to listen, cajole, guide and encourage. Constantly.

This means that, in reality, design system teams are in the business of change and people management. And this, by proxy, means that you’re in the business of communication, often across a sprawling org who’s employees (your users) have limited bandwidth or attention as they’re focusing on their priorities and not those of your design system.

How you manage this communication effectively is a whole post in itself.

However, in a nutshell I believe you need…

- Clear documentation around how to use the system

- Obvious ways to access support when users don’t know what to do

- Clarity around end-to-end governance processes

- Mechanisms like guilds or council to help users discuss or share new components or work together on modifying existing ones

- Ways to demonstrate the value of your design system both to potential users and to leadership.

5. Community matters

If people are your product, then that means you need to be able to rely on them.

There needs to be a sense of collective ambition and toil towards shared outcomes.

You need to work hard to get people bought into an almost utopian all-for-one and one-for-all mindset in which we build with reuse in mind, putting the greater good ahead of our own selfish ends. You also need to be prepared to encourage people to help stand by their fellow worker’s support requests when they don’t understand why the component they built two years ago isn’t working as they expected.

How do you build community? There are a few things that come to mind.

- A clear purpose for the design system that folks can get behind.

- An ethos that encourages working in the open and taking other teams along with you on the journey.

- Forums for public dialogue, support requests and open ideation that are well attended and vibrant.

- The encouragement of evangelism.

WebCore’s community spirit is a key pull for its members. There are tonnes of knowledgeable individuals and teams that are willing to help out others building into the design system or taking something from it. There are open Slack channels that anyone can use to ask questions about how to use a component, seek help or knowledge or pitch a new idea.

We also rely heavily on a fortnightly Community Call that acts as the design system’s townhall and, this year, have launched the concept of Design System Advocates – a group of evangelists from outside the design system team who, in exchange for advanced training and the opportunity to shape the future of the design system, invest time and effort in creating and encouraging best practice from the wider community and suggesting and implementing plans to improve the design system and its processes.

Design systems are people-powered and people need community.

6. People love design systems. People hate design systems

Having not worked in the design system space before, I started off by researching as much as possible.

I quite quickly found there was a growing community of people working on design systems that were openly talking about their work online.

This was great for me. Lots of people are incredibly passionate about this work and are trying to work in the open to spread good practice with others and help one another. There are great design system podcasts, training resources, online events, meet ups, Slack channels and books. I tried (and keep trying) to absorb as much info as possible.

Not gonna lie, there was that much information it felt kinda overwhelming so I was super grateful to kind folks such as Ellis Capon, Scott Strubberg, Marianne Ashton-Booth, Robin Cannon, Steve Messer, Dan Donald, Grace Han and Amy Hupe who were kind enough to give me some of their time and wisdom. They all said variations on the same theme, this is a complex space, be patient and kind to yourself.

So, that covers people loving design systems. But what about people hating them?

Well, as much as design system folk love the concept and can see the benefits, working in the design system world is still incredibly challenging because of the people / change side of things. These challenges may include convincing your org’s leadership that they should invest in having a design system in the first place, or trying to encourage colleagues that building into a design system may take initial effort but that will lead to greater efficiencies in the long run or trying to encourage those already using a design system to stick to agreed best practice. Sometimes working in spaces like this, where you can see the benefits but your job is to constantly convince or course correct others can, to be honest, feel draining and repetitive. It definitely takes a certain type of person with a high degree of resilience.

I think this is why the wider design system community is so vocal, active and supportive of one another. It certainly does help too.

7. Demonstrate value and celebrate wins

This aspect of design system work, the constant convincing and seeking of buy-in has can frequently contribute towards both team and individual burnout.

Plus, design system work frequently relies on cross-team collaboration, often across a big organisation which, as you can imagine, can lead to the work feeling slower than if you were just building products and features.

What I’m getting at is, sometimes design system work can feel a little thankless, if you let it.

At a point in which I was feeling particularly deflated, I saw Amy Hupe give a talk at the wonderful Converge Festival on the importance celebrating your wins.

I found the talk inspiring and since then have tried to create a culture that celebrates our successes as a team both internally and externally.

So, what does this look like in practice?

Whenever we complete a significant piece of work, or help other teams unlock value via the design system, you can bet on us hitting up the company Slack channels or putting a blog post together. Often times, the design system lets other teams build new experiences faster than they would have been able to without it. When new releases happen within the company, we try to speak to the team and find out how much they relied on the design system or collaborated with other teams and create content around this to both promote the value of the design system and encourage more similar behaviour in others. Doing so helps to show others in the company the value of design system and goes a long way towards encouraging wider buy-in.

However, what is equally important is celebrating our wins within the team. The team I’m in is full of some of the brightest, most committed and intelligent people I’ve had the pleasure to work with. Giving kudos to one another and calling out and celebrating what we’ve achieved both individually and collectively really helps. It is necessary to pep one another up to maintain the required reserves of motivation, morale and energy often needed to work effectively in design system world.

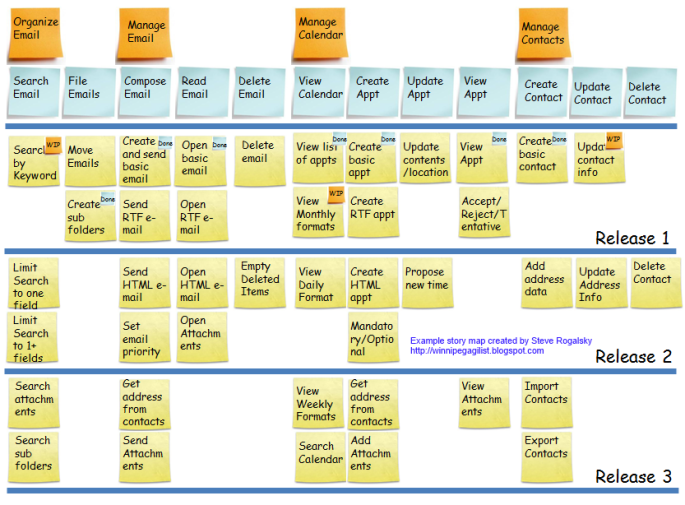

8. Governance? Yes, please

A lot of the job is making it easy for others to use the system.

This often means governance is required.

For example, a team is just about to create a new user experience. They aren’t sure whether they should use a component that’s already in the design system as it gets them 90% of the way there or create something from scratch.

How do they make that decision? Who do they need to talk to? And, if they decide they want to use what’s there but slightly tweak or amend it, how do they go about communicating the purpose and need for their proposed change to the wider community?

Its ironic, design systems exist to bring about efficiency by reducing the need to resolve problems. But, without clearly defined and communicated governance processes, you’re asking users to reinvent the wheel each time they want to figure out how to achieve something using the design system.

Recently we’ve spent a lot of time and energy improving and clarifying our governance processes and, although communicating them and encouraging wider adoption will be a long game, we’re certainly seeing early successes. What’s more, users are telling us they’re grateful for us doing this work, a lot of which has been done with input from the whole community, especially the Design System Advocates.

This was interesting as we had a lot of conversations about not wanting to be the design system police. However, what we actually found when digging into this is that people working on a design system want and need governance to make it easier for them to work. Rather than feeling like we’re bossing people about, they’ve told us our role is to make it clearer what the rules are and how best to proceed.

Rather than the design system police, we’ve taken to viewing ourselves as the gardeners of the design system, our role is to create a harmonious space through pruning and growing, and, by doing some occasional weeding too when stuff you might want tries to find its way into the design system.

9. Metrics ftw

The design system space is quite famous for not being great at telling a compelling story through numbers.

This is a shame, as we’ve discussed not resolving the same problems multiple times = baked in efficiencies and savings for the org.

Therefore, I feel the design system world needs to get better at demonstrating the ROI of having a design system.

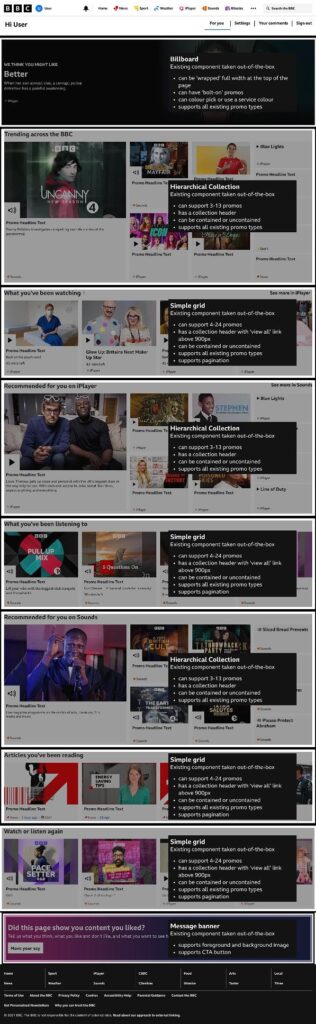

One of our early stabs at trying to show the design system’s value was to analyse the role it played in launching the BBC’s For You experience.

We discovered the team behind the page, a key pillar in the organisation’s personalisation strategy, was able to create take the experience from concept to market in a matter of weeks owing to the ability to pick up high-quality and reusable components that already existed in the design system.

We gave a huge amount of kudos to the team for following great practice in terms of trying to build new experiences by using what already exists in the design system. That team, having got something out to users quickly, are now looking to iterate and improve the experience and are likely to create new, innovative features and components that don’t exist right now in the design system and therefore, when created, will provide value to all the other teams that can them have access to them too.

We were delighted to be able to tell this story, but our goal in the near future is to be able to tell stories such as this without as much manual investigation and with hard numbers attached.

We’re working on getting automated access to a number of metrics we can use to measure and improve the performance of the design system, tell better stories and make data-driven decisions.

These include knowing things such as speed-to-market, speed-to-prototype, components used by the most/least amount of other teams, components seen by the most / least amount of audiences.

We’re excited to eventually get access to this data in order to better demonstrate the value our design system provides to the organisation and encouraging wider and deeper cultural buy-in.

Thanks for reading

If you’ve found this article helpful, why not sign up to the newsletter, or subscribe to Product Confidential, a product management podcast I co-host with Evie Brockwell.