My lovely team taking part in a user story mapping session – the main focus of this piece.

In my previous article I discussed what an MVP looks like in government and that, whilst they are not a true MVPs, defining one is still an essential requirement to moving your team in the right direction.

In this article I aim to get amongst the weeds and discuss how you actually go about defining your MVP.

The article will focus on a technique called user story mapping and briefly touch on how you can use visualisation techniques to help bring your stakeholders on the journey.

Some important prerequisites

Before you can effectively use user story mapping, it’s advisable that you have done the following things.

- Ran a discovery to understand the problem space and the user needs that you are trying to solve.

- Created an as-is service blueprint that shows the current process users must navigate, making it easier to visualise where your product can add value.

- Go through an alpha stage to devise and test some concepts that you may use to meet user needs.

- Agree upon the winning concept that you can develop into the MVP you plan to release in order to test and learn from.

Before we get into user story mapping, I just want to clarify something.

If you’ve agreed upon the winning concept in the alpha stage, why do you still need to define the MVP?

Well, in my experience, even when the concept has been agreed upon, there likely to still be debate within the team over how to best implement it, or around which features are truly necessary for the first release as opposed to being nice-to-haves that can come later.

Here’s where a user story mapping session is really useful and can help your team nail down what’s going to be included within the MVP by teasing out some interesting conversations.

User story mapping

User Story Mapping is a technique associated with Jeff Paton and is, in his own words ‘a simple idea’.

One that I’ve found to be unparalleled system in helping teams showcase the entirety of their product, build shared understanding and simplify complexity.

What is user story mapping?

It’s a process that will help your team to visualise your product’s features in it’s entirety, including features you want to launch with, plus what to expect from later releases.

How do you run a user story mapping session?

I prefer to do user story mapping in a room using post-is but you could just as easily use a digital whiteboard. Try to make it a collaborative session in which attendees agree upon what user stories are needed to help meet the needs that have been identified in your discovery, and the order in which they’ll be met within your product.

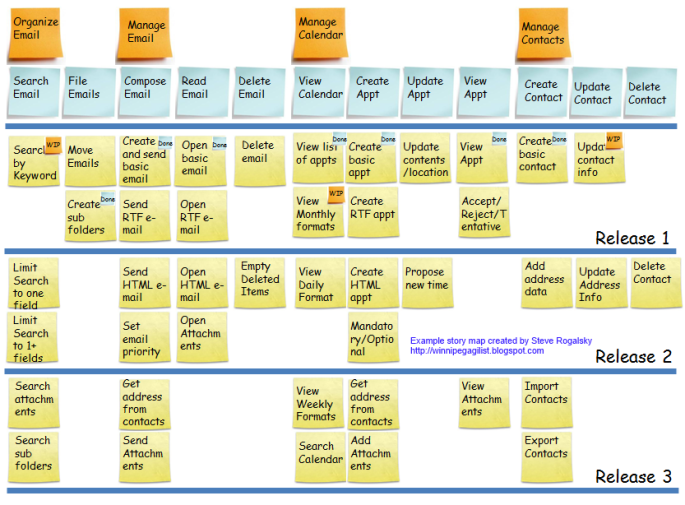

On the board you’ll have your top-level row running from left to right that will have your high-level tasks, or epics.

Underneath that you can have the tasks a user will need to take to complete your epic.

And finally, underneath place the features (or user stories) that are required to enable the user to complete the tasks.

The task will be for you and your team to firstly agree the epics, and then work your way down the board row by row, agreeing what user tasks and stories are needed to complete each epic. What you’ll be left with is a top down view of your whole product from the perspective of your user.

Top tip for running the session.

Have an icebox section in which you pop ideas for the future or questions you may need to answer or consider. Reason being, as you go through this process you may find it triggers some amazing thoughts and discussions within your team. And whilst that’s all well and good, it is handy to have a way to put a pin in discussions that are going too far off track whilst also making a note so you don’t lose cool ideas that may come in useful down the line.

Below is an example of the end result of a user story mapping session.

What does story mapping help you to do?

- Walk through the whole user journey and see the bigger picture.

- Visualise the MVP and help the team build a shared understanding.

- Unearth fantastic conversations about the product that may not otherwise have surfaced, especially around prioritisation.

- Prioritise what features are required for MVP whilst also defining your future roadmap of releases.

- Define how your solution will meet the needs identified in discovery / alpha phases

- Understanding dependencies and showing where you may have blackspots or unknowns in your user journey.

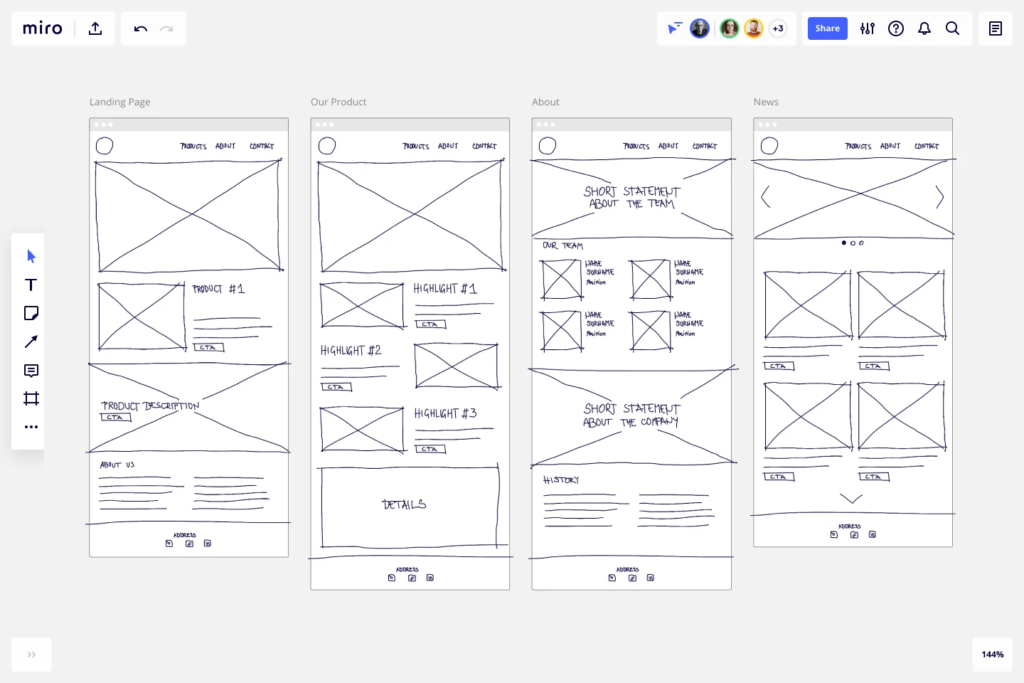

Visualising the MVP

Whilst the user story map that you’re left with is a helpful exercise to go through and will leave you with an asset that your team will understand, I personally feel the end result is perhaps a little off putting to stakeholders.

That’s why, I recommend supplementing this work with low fidelity hand drawn wireframes that you can use with stakeholders to bring to life what you and the team have in mind in an accessible fashion.

Did you find this article useful?

If so, I urge you to do a number of things (should you wish to)

- Sign up to the newsletter and receive new posts straight to your inbox

- Follow me on LinkedIn or Twitter

- Share the love and post this article on your social media accounts